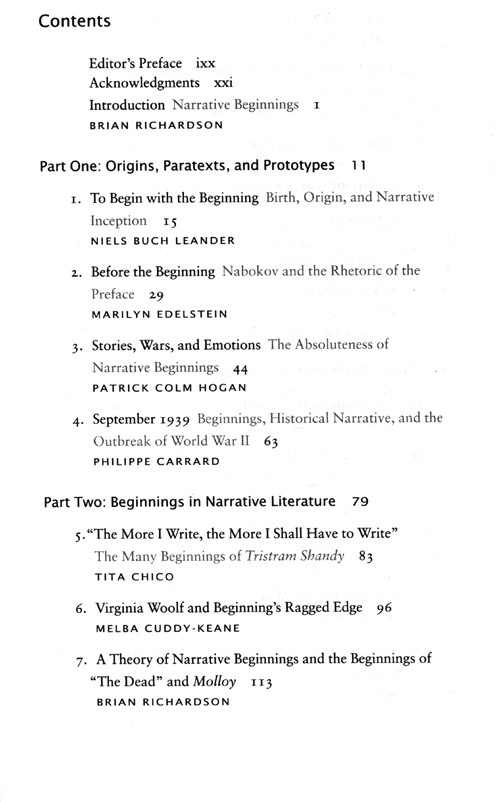

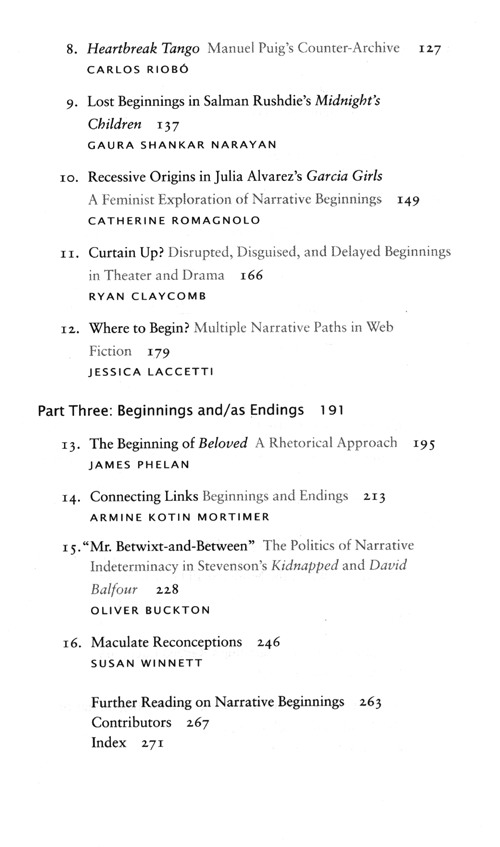

《叙事开端:理论与实践/外国文学研究文库·第三辑》:

This selection then combines with our tendency to segment and structure causes in terms of malevolent or benevolent intentions, with some bias toward malevolent categorization. One result is the common specification of narrative beginnings in terms of malevolent actions. We find this to some degree in the standard beginnings for all three cross-cultural narrative prototypes: romantic, heroic, and sacrificial tragicomic.12 For example, in the standard romantic plot, the lovers are initially separated by an interfering parent. For our purposes, the most important of these three prototypes is the heroic, because our employment of wars is precisely an employment in terms of the heroic prototype. That prototype manifests the malevolent initiating moment most starkly. Moreover, it synthesizes our tendency to view causality as dispositional (i.e., to understand it in terms of benevolence or malevolence) with our parallel tendency to categorize human agents into in-groups and out-groups. Specifically, it sets out a malevolent attack by an out-group-usually an invasion by a foreign power-as the absolute and singular origin of the central narrative conflict.

Beyond these matters, which bear directly on narrative beginnings, our cognitive dispositions have other consequences for our (narrative) understanding of and response to war as well. One result is that we tend to experience our own emotionally guided response to the "initiating event" as compelled by the event, thus not morally blameworthy. This is particularly true when we have no attentional focus on the harmful consequences of our acts (e.g., enemy casualties that would trigger empathy by way of mirror neurons). In contrast, we tend to see the malevolent actions of the out-group as chosen. They are not caused by prior events, but rather derive from group properties. Thus their actions are not only immoral in themselves but reveal an underlying immorality of shared character (racial, cultural, religious, national, or whatever).

A second result is that arguments against absolute and singular origins for conflict strike us as similar to the arguments of out-groups. Specifically, we tend to categorize such arguments as positing a different origin for conflict rather than as disputing origins per se. Because of the cognitive and affective constraints on our spontaneous causal understandings, we readily assimilate such arguments to justifications for the out-group actions. Simplifying somewhat, we might say that our spontaneous causal attributions give us two obvious alternatives our own version of causal attribution and a parallel version offered by the out-group. If these are the two options, then any argument that is not of the former sort would seem to be of the latter sort. Of course, in many cases, attacks on antiwar arguments are duplicitous. Politicians know perfectly well that, for example, antiwar protestors are not supporters of Saddam Hussein. However, the point is that the objective illogic of their objections to protestors can be broadly persuasive due to our cognitive propensities.

The preceding point is enhanced by a final consequence of human emotion; specifically, insofar as they involve strong emotions, our spontaneous attributions of causality may remain at least partially impervious to our knowledge about actual causal relations. In other words, our emotion system may continue to spontaneously project a single, absolute, malevolent origin to conflict, even when higher cortical systems have inferred that this is not the case. Again, this results from two complementary factors. First, our emotional responses may usurp working memory, thus the very inferential processes that should inhibit our spontaneous causal attributions. Second, our lack of emotional involvement with alternative analyses (e.g., our lack of emotional involvement with the projected causal agents, thus the out-group) means that these alternative analyses receive no further attentional focus or elaboration and thus are unlikely to engage inhibitory processes.

……

展开